Quick! What does the green light at the end of the dock mean for Gatsby? What is the significance of the colored rooms in Poe's “Masque of the Red Death”? There are lots and lots of guesses, and lots and lots of critical papers even about such things, but honestly, only Fitzgerald and Poe know for sure. And that's just fine. The reason these two stories continue to resonate with people is because of the mysteries they still hold.

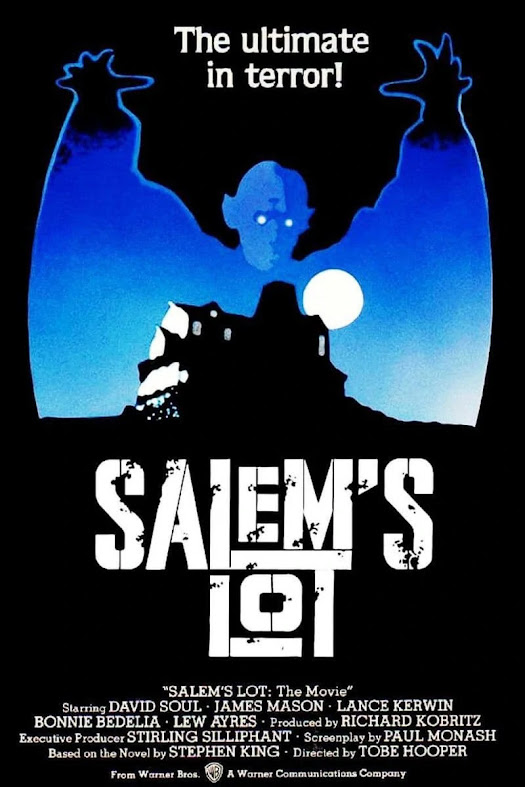

Fine, fine, fine. Those are literary masterpieces. What about popular fiction? Okay. Challenge accepted. I'll go as low-brow as movies. Is Decker a replicant or not? Are you sure? What's really going on with the titular Spider Woman in that movie about her kiss? Is “the shape” in the original Halloween killable or not? (Before the endless sequels, of course.)

See? Mysteries.

And not just the “Was it Colonel Mustard in the dining room with a pipe wrench?” kind of mysteries (though those can work too.)

The best stories, and again, as with any essay on this blog, in my heavily read and studied opinion (vanity, thy name is Sean), all leave a bit of mystery unsolved for the readers, whether in some character's story (What is Ned Land's story?), some symbol that isn't defined (Is the rain really a stand in for sex in this scene?), some action unexplained (What did he say to her in that aside the author didn't reveal?), or some thematic idea unspoken (If good triumphs over evil, why did Hannibal escape?).

And we can learn a lot from them.

Yes, yes, I know. We live in a world of best-sellers and Summer blockbusters where every secret is supposed to be revealed by the end of the final act and we fill in all the blanks for our audiences. After all, that's what modern readers want, right? Everything wrapped up in a pretty little bow with the right tag and a proper message on the card so it gets delivered to the correct person who can open it up and suddenly make sense out of everything he or she or they has seen or read. That's what publishers look for, neat little bows. All the ducks in a row. All the questions answered.

But think about it for a few moments... What if we didn't?

Why mystery?

There are lots of great reasons to leave mysteries in your work. I'll cover just a few of them hear. Feel free to explore the rest of them in your own writing and reading.

1. Mysteries allow the writer to hide inside the work.

Typically writers tend to not want to directly inject themselves and their opinions into their work in order to avoid writing propaganda, and when they do, they tend to avoid mystery. I'm looking at you, Narnia and Atlas Shrugged. But if you look deeper, there are plenty of amazing works of both literary and popular fiction that have a lot to say—maybe or maybe not. And that's because the writers who created them embraced the mystery.

Some might call this subtlety instead, but it's more hidden than that. It's almost like one of those hidden eye puzzles from the 1990s that were so popular. If you learned the trick, most people could see the hidden picture in all the weird zig-zag patterns. But, if you have an astigmatism or just the wrong level of near-sightedness or far-sightedness, you were screwed from the get-go. Try as you might, you just weren't going to be able to see that horse, or sea turtle, or “I love you, mom!” in calligraphy.

And that's how this kind of mystery works. If you're the right target, you probably see it, but you'll never quite understand if it's just something you're bringing to the story yourself or if it's really there.

A case in point—

The Rocky Horror Picture Show. I know, I know. The epic high point of literature, right? Regardless, I have a strong opinion that this movie is about a hell of a lot more than just two prudes who get stuck at the secret lab of a transsexual alien. I hear you saying, “Of course it is, stupid. It's about LGBTQIA+ people being trapped and unable to truly be themselves in an American patriarchy. I think while it may also be about that, what it truly has to say is something that remains more hidden, a mystery if you will allow me. That mystery is this: When the sexual revolution is all said and done, the only people to survive it were women. The revolution happens, but traditional maleness like Rocky and reckless individualism like Frank are quick to pay the price. Even Brad, the bastion of patriarchal mores and values is broken (“Help me, Mommy!” he sings). Only Janet faces the revolution and survives, thriving even finally.

Rocky Horror is about how women won the sexual revolution of the 1960s and early 1970s.

Am I right? Who knows? Who cares? The important part is that the mystery allows me to play with notions that perhaps Richard O'Brien was trying to hide the story of Rock-n-Roll giving way to Glam Rock in his screen play. Or maybe it was only about LGBTQIA+ feelings all along and that was all. Or maybe it was about the conflict between nostalgia and moving forward into new types of stories. It doesn't matter. O'Brien's views are so deep in that screenplay we may never know, but they're shrouded. They're open for everybody to take a guess. And that's okay.

A few other examples from actual books, for you more high brow types:

– Political Views –

Dickens' perennial classic, A Christmas Carol, isn't just a a fun holiday ghost romp about a mean old miser. It's a political jab at the views of Thomas Malthus. Malthus believed that if people took care of the poor, then they would just continued to procreate and eat up resources. Best to let them starve or work themselves to death and stop using the resources that should be reserved for the industrious providers or the well-off. (I know; sounds familiar today, doesn't it?)

Sophocles, in his play Oedipus at Colonus, is taking pot shots at not just how Greek culture is declining, but why it is declining and how the leaders are pressing the gas pedal on the chariot toward hell.

“Does Sophocles actually say any of these things? No, of course not. He's old, not senile. You say these things open ly, they give you hemlock of something. He doesn't have to say them, though' everyone who see the play (Oedipus at Colonus) can draw his own conclusions: look at Theseus, look at whatever leader you have near to hand, look at Theseus again—hmmmm (or words to that effect). See? Political.” —Thomas Foster, How To Read Literature Like a Professor

– Social Views –

What about traditional religious and cultural rules that trap people into loveless and disastrous marriages? Look no further than Eudora Welty's Ethan Frome or Kate Chopin's The Awakening. With Chopin you also get the added value of early feminism. How about The Bell Jar? Or The Catcher in the Rye? Too fancy for you? Okay. How about Bradbury's cultural beliefs in mankind's rebuilding on another planet in The Martian Chronicles? Or even H. Rider Haggard's evolving views of might makes right between Allan Quatermain and She and the softening of the great white right to expand in later works. And what is E.R. Burroughs saying about the rugged individualism of American male unstoppable-ness in his Mars series?

– Religious Views –

Compare the religious allegories of C.S. Lewis to the religious metaphors and mysteries of J.R.R. Tolkien. Lewis dots all his “i”s and crosses all his “t”s so the point isn't lost or even having to be thought about. Aslan is God and Jesus. You got that. Good. Don't forget it.

But who is Gandalf? God? Sometimes. Jesus? Well, he does come back from the dead in white robes. Is he a fellow traveler? Sure. Okay. Who the hell is he? And don't even mention the returning king or the friend who sticks closer than a brother? Confused yet by the religious mysteries in the work? Don't worry. It's entirely intentional. Much to Tolkien's credit, he doesn't answer the questions. He lets the mystery linger in the mind of the reader. But can we be sure it is there intentionally? Don't forget that Lewis and Tolkien regularly got together at the pub with the rest of the Inklings to drink and discuss literature and religion and politics and writing.

But who is Gandalf? God? Sometimes. Jesus? Well, he does come back from the dead in white robes. Is he a fellow traveler? Sure. Okay. Who the hell is he? And don't even mention the returning king or the friend who sticks closer than a brother? Confused yet by the religious mysteries in the work? Don't worry. It's entirely intentional. Much to Tolkien's credit, he doesn't answer the questions. He lets the mystery linger in the mind of the reader. But can we be sure it is there intentionally? Don't forget that Lewis and Tolkien regularly got together at the pub with the rest of the Inklings to drink and discuss literature and religion and politics and writing.

Bear in mind, though—and I can't stress this point enough—that none of these interpretations are stated. None are set in stone. (Except for Lewis' Aslan.) They are all inferred, not necessarily even implied. They are mysteries in the subtext. And they keep the works fresh in the minds of readers and on the shelves of bookstores each year.

2. Mysteries allow readers to wonder.

Good mysteries put a question into a reader's mind. Great mysteries worm their way into a reader's brain one centimeter at a time, gnawing and licking at the soft tissue of the brain and pushing each stray thought to the side to gain dominance over all the synapses so that the mind can focus on one question alone—my question.

Great mysteries are the kind that make you talk about a movie after you are driving home from the theater. “Was Darth Vader the necessary evil to balance a force that was leaning too far to the good side?” “Is Baby Doll in her real reality when she was lobotomized or could it be just another, more realistic dream?” “What actually happened to Lucy when when transcended her human form?”

Great mysteries are also the kind that keep readers talking about a book when they are online or at their writers group or sitting around the basement doing homework.

Yes, even YOUR book.

But they don't work if you don't write them into your work. And they also don't work if you answer them and fill in all the blanks for readers.

We see it all the time in series fiction. Will they or won't they? Oh, look, they like each other now. I wonder what will happen in the next book. Oh, crap. His wizardess fiancée showed up. I thought she was dead. How will they move past this one—and solve the current dilemma of course.

But what about non-series fiction? And what about fiction that isn't so plot driven or is so plot-driven it doesn't have time for those kind of questions. Well, stick in pin in that right there because you never are so plot-driven that you don't have time for mystery. It just has to be subtle.

For example, in Ian Fleming's 007 novels, you never really wonder if Bond is going to get out alive. That's a given. But what about one of those side characters that Bond actually cares about. What if Moneypenny gets in trouble somehow and that figures through a few books? What if a love interest manages to survive and come back to visit in another volume? No, I doubt you'll see that happen in a Bond book, but it could very well happen in yours.

Just think of the “what if” questions you could plant into your readers minds.

3. Mysteries allow readers to pick a side.

If you really want to see your fiction live forever, let your readers pick sides in an argument about the mysteries that you choose not to spell out and put into a convenient box.

For example, let's look at the room colors in Poe's "The Masque of the Red Death" referenced above at the beginning of this article. Pretty much since the time that story was seen by readers, people has argued about what the colors symbolize. Is it the seven deadly sins? Is it moods and psychological issues as thought by post-Freudian critics? Is it just a random collection of colors that doesn't mean anything? Don't expect those arguments to be ever really be settled for good. Poe was a genius. As long as people disagree on his unsolved color code, that story will continue to live in the public mind.

For example, let's look at the room colors in Poe's "The Masque of the Red Death" referenced above at the beginning of this article. Pretty much since the time that story was seen by readers, people has argued about what the colors symbolize. Is it the seven deadly sins? Is it moods and psychological issues as thought by post-Freudian critics? Is it just a random collection of colors that doesn't mean anything? Don't expect those arguments to be ever really be settled for good. Poe was a genius. As long as people disagree on his unsolved color code, that story will continue to live in the public mind.

Now, you may not have the clout of Poe or Fitzgerald or Fleming or Dent, but you do have readers, and if you want them to remember your work forever and ever, till death do you part, consider helping them break into camps and argue with each other about what you mean by that character or that location or that plot point.

This works because all people have an innate desire to be right—especially about their own opinions. Play into that. But remember... DON'T WRAP THE ANSWER IN A BOW AND GIVE IT AWAY. When you give the answer, the argument stops. People stop talking about and thinking about your puzzle.

Let's look again as something like Sophocles, referenced above:

“Was the cave symbolic? You bet.

"Of what?

"That, I fear, is another matter. We want it to mean something, don't we? More than that, we want it to mean some thing, one thing for all of us and for all time...

“What the cave symbolizes will be determined to a large extend by how the individual reader engages the text. Every reader's experience of every work is unique, largely because each person will emphasize various elements to differing degrees, and those differences will cause certain features of the text to become more or less pronounced. We bring an individual history to our readers...”

“One of the pleasures of literary scholarship lies in encountering different and even conflicting interpretations, since the great work allows for a considerable range of possible interpretations.” —Thomas Foster, How To Read Literature Like a Professor

One of the best tools in your writer's toolkit is the puzzle creator and one of your best writer super powers is the ability to portray images and events that can mean different things to different readers.

4. Mysteries allow a story to stick with readers after they close the book.

Let's look at a few memorable books and movies that have stood the test of time and the questions they leave with readers or viewers:

- John Carpenter's The Thing – Which of the two survivors is harboring the creature? What of neither of them are? What next?

- Roman Holiday – But couldn't they have gotten together if... Will they both be forever unhappy?

- A Farewell to Arms (the book, not the movie) – what happens next to Frederic? Was the universe really out to get Frederic and Catherine for trying to be existentially happy?

- The Wildcards series – how will the Aces ever rebuild real credibility? Can the Jokers ever get genuine acceptance?

There's a wonderful little (or not so little) epic fantasy series by one of my wife's favorite writers, Stephen Lawhead, called the

Song of Albion trilogy. One thing about about that series that has always puzzled her though is the introduction of a family in the first volume that helps the main character get from point A to point B in the plot. Then they disappear. My lovely, literate bride spent the entire series looking for that family to appear again and discover their grand purpose in the story—because clearly they had one. Right? Did Lawhead simply forget about them? Did he feel they had served their purpose and didn't need any further "screen time"? Or did intentionally leave their story untold, knowing it would make my poor little wife's head shift into overdrive to wonder about long after she had closed the book on the series and moved on to Cadfael or Evan Evans?

I used to believe it was an accident, that Lawhead simply forgot about them and let them fall into the cracks between the pages. But the more I thought about it, the more I began to lean toward it being an intentional omission. I believe there story was simply a single point of intersection and that by making the family interesting it would compel readers to wonder about them, particularly to wonder enough to pick up books two and three in the series.

It's a mystery.

Why do the mysteries like those covered in this article live on in readers' heads after the books are closed and put back on the shelves? Precisely because they are unanswered, lingering, hinted at but not expounded upon, barely shown but kept interesting, "squirrels" that cause the readers' focus to shift and chase through the yard.

But how do you do that as a writer?

Well, for starters:

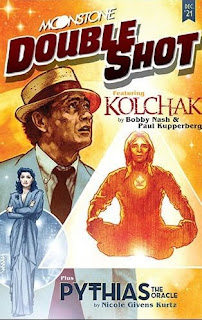

- Untold backstories for interesting side characters

(Where did that reporter she used to date come from? What was their time together like?) - Symbols that don't have specified meanings

(Gatsby's light, Poe's paint jobs) - Actions that seem initial out of character

(Why would a big softie like him do THAT?!) - A lack of denouement

(So, what happened to the femme fatale who wasn't the killer?) - The unexpected and lesser preferred ending, i.e. the "WRONG" ending

(Why didn't they get together, you big meanie?) - The third act resolution introducing new issues that don't get solved

(Wait... If that's whodunit, then what will happen to the butler after all?) - World-building issues that aren't part of the main plot

(What about that poverty-stricken part of town; is the hero going back there to help or not?) - Lack of clarity in the resolution

(Is the heroine in her right mind now... DUM, DUM, DUM... or is it just another multiple personality?) - Turning a key symbol around in the last act

(What if Aslan wasn't really God after all, but an imposter?) - Symbolic bits and bobs that are secretly the writer's opinions about religion, politics, culture, etc.

(Does that chain on the hero's car mean he is hampered by his caste or not?)

This is just a starter list. The more you exercise this part of your brain as an author, the more avenues you will see open up to you.

What now?

.jpg) So, you see, the important thing in all of this is to keep those meddling kids from actually pulling the mask off and revealing the secret.

So, you see, the important thing in all of this is to keep those meddling kids from actually pulling the mask off and revealing the secret.

Hopefully, this little introduction has started or helped you keep thinking about letting mysteries remain mysterious in your work. Or maybe for some of you, actually weaving some mystery into your stories. Or just looking for them in other books and movies as you read and watch to help you continue to grow in this area of writing.

The key is to remember that poor dead/alive kitty cat in Schrödinger's famous box. Nobody knows anything for certain until that box gets opened. And as long as you are doing your job as a mystery-creating writer, you're going to do your damnedest to hide all the scissors and utility blades in the house, so that the stupid box never gets opened.

%20Words.png)

.jpg)

.png)