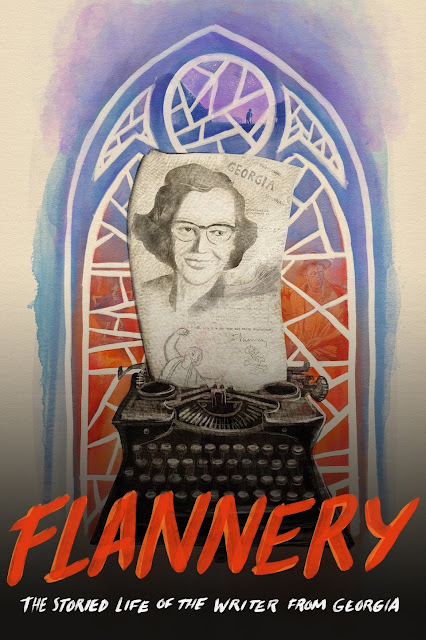

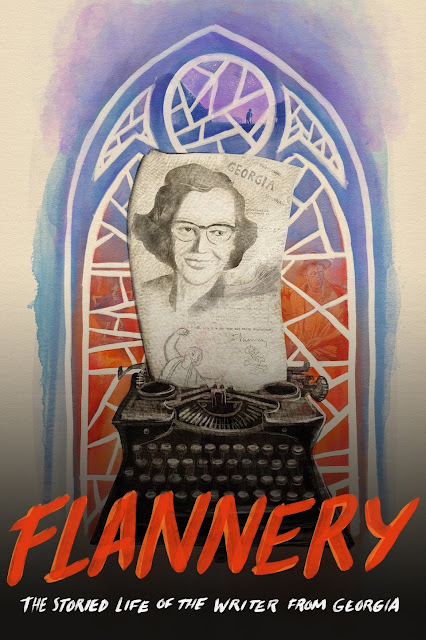

Flannery O'Connor is not only one of my favorite writers, but she's also the subject of a PBS documentary named after her. Known as perhaps the Grand Dame of Southern Fiction, O'Connor is THE voice to be reckoned with in the world of fiction seen through the eyes of the South.

But she wasn't what she seemed, neither a Southern lady nor a rebellious feminist. In fact, according to Conan O'Brien, discussing her and her work in an interview: "You think it's this bitter, old alcoholic who's writing these really funny dark stories, and then you find out she's a woman and that she's devoutly religious." Her work and her life didn't always line up with straight edges. There was overlap, and there were gaps where they didn't quite join up like they should.

But to limit her to merely a Southern writer, as Harvey Breit says, isn't fair to her legacy:

I for myself think that although Ms. O'Connor can be called a Southern writer, I agree that she's not a Southern writer, just as Faulkner isn't, and that they are, for want of a better term, universal writers.

They're writing about all mankind and about relationships and the mystery of relationships.

To Flannery, that universal mystery she was writing about had a lot to do with craziness, according to Alice Walker:

She was able to go straight to the craziness without always trying to make the craziness black or the craziness white.

She just saw the mystery of the craziness.

Like any good and gifted writer, she embraced that craziness and darkness and humor within her. She embraced all of herself, the dark and the light, and that's what made her fiction stand out. Says Richard Rodriquez: "What's happening here is something so remarkable that the profane meets with the sacred, and it's within that comic meeting that the stories operate."

It's a place many writers don't reach for a long time, having to first discover who they are through their writing first. Hell, some writers never get there. They may hide one part while focusing on what they think readers want to read. They may hide all of themselves and chase markets. But all truly talented writers eventually learn that your best work doesn't happen, can't happen until a person's fiction integrates all the parts of the one doing the writing.

It's the clips from during her life that make this documentary so much fun. One stand-out moment comes from a television show in which she is asked to talk about the art of short stories.

Breit: What does a writer try to do in a short story? Or what does a writer try to do in a novel? What is the secret of writing?

O'Connor: Well, I think that a serious fiction writer describes an action only in order to reveal a mystery. Of course, he may be revealing the mystery to himself at the same time that he's revealing it to everyone else. And he may not even succeed in revealing it to himself, but I think he must sense its presence.

As a writer who prefers short stories to any other literary form, both for reading and writing, i think she's dead-on in her assessment. But I don't think it only applies to "serious" fiction writers. I think all writers have a subconscious writer living inside their heads that works that kind of thing into even so-called popular fiction or genre fiction. I tend to believe it's the kind of thing a writer can't avoid ultimately.

Throughout the last years of her life, having been diagnosed with Lupis, the same uncurable disease that killed her father, the "all of her" that made up her life got progressively darker. However, that only reinforced her will to write, to create, to tell stories. According to Hilton Als, "I think she loved writing so much because it freed her from the corporeal." Writing was her escape from pain being tapped by her body. Creating was her winged bird (thank you, Langston Hughes) that was free to fly her imagination beyond her diagnosis. Telling stories was her way of travelling the world since her weakened body wouldn't allow that dream to come to fruition.

The documentary spends quite a lot of its run time on her time writing Wise Blood (my favorite of her two novels). Her first novel, it was important to her to get it right, to capture her darkly comic intersection of realism, grotesque, and religious. In fact, according to Michael Fitzgerald, she ended up going back to rewrite from the beginning after reading and being so taken by Oedipus Rex. Says Michael: "She was so shocked by the Oedipus Rex that she reworked the entire novel to accommodate Hazel Motes' blinding himself, as Oedipus does."

In a discussion between Robert Giroux and Sally Fitzgerald, the two share this exchange about how her own thoughts on Wise Blood and those of her publishers and the reviewers didn't mesh.

Fitzgerald: I think you can see in her letters about working on Wise Blood and the process that she went through, her first publisher who didn't get it.

Giroux: Flannery said that, 'The editor at Holt treats me like a dim-witted campfire girl.'

Fitzgerald: He called her prematurely arrogant.

Gooch: And O'Connor, very young, I mean, completely stands up for herself and the possibility that this book will never be published and just says that, 'I'm not writing this kind of novel.'

Fitzgerald: Publishers never intimidated her.

Mary Steenburgen (reading from O'Connor's journal): I am not writing a conventional novel, and I think that the quality of the novel I write will derive precisely from the peculiarity or the aloneness, if you will, of the experience I write from.

This isn't uncommon. Our intentions as writers and what readers and (worse) reviewers read can be polar opposites. The ladies of her Southern small-town life saw the book as vulgar and actively irreligious, failing to notice the ragged shadow that followed Hazel Motes around with every step and wouldn't let him get away from faith no matter how he tried. Others simply saw some of her dialog as "proof" of her own racist beliefs and wondered how a sweet Southern lady would write such things into the mouths of her characters.

Some of the fault in that misunderstanding, according to Richard Rodriquez, comes from O'Connor's immense talent as a dialog writer and her ability to capture voice even in internal monologue.

Part of my worry as her reader is that she's too good, by which I mean that her mimicry of her voices around her is too acute.

In that accuracy, she doomed herself, because a lot of these stories are judged by modern readers as unacceptable.

Still, even with ticks against her, Flannery O'Connor's legacy is secure. I don't see "A Good Man Is Hard To Find" or "Everything That Rises Must Converge" disappearing from textbooks or bookshelves of voracious readers any time soon. Perhaps this quote from William Sessions best sums up her writing life:

The life of Flannery O'Connor and what she had to offer, in terms of her relationship to the greater mysteries of existence, are going to be things that people will tap into, because they aren't going away.

God, how'd I love for someone to honestly say that about my work one day.

No comments:

Post a Comment