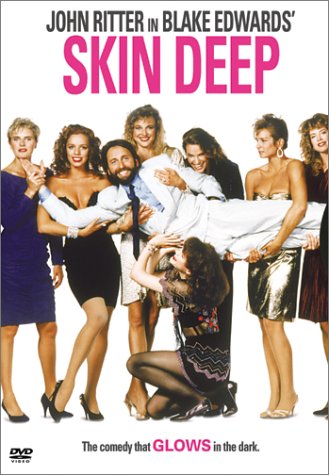

This is clearly Blake Edwards territory. Know that before you go in. It even has a gag with a glow-in-the-dark condom swordfight. But it's so much more than that too, just like a Blake Edwards film. Beneath all the sex jokes it actually has something worthwhile to say.

Zach, played by John Ritter at his comedy best, is a best-selling writer who has lost 'it' and can't find his muse anymore. Granted, he's too busy looking into the beds of random women and at the bottom of bottles of alcohol.

The opening scene puts it all right out in front. It doesn't hide anything. Zach is having sex with the woman who is cutting his hair when he is discovered by his mistress, who then is discovered by his wife, Alex. Bam. There it is. Pissed, Alex tosses his typewriter out the window.

This sets up the single most important bit of dialog in the flick:

Zach: What have you got against my typewriter?Alex: You used to write on it. Books and plays and movies. Once -- once you wrote a poem on our second anniversary and gave it to me. And you were happy. You exorcised your demons with credible thoughts and good words on that typewriter and your talent turned me on. I really thought we had a chance "until death do us part." And then one day you stopped. You gave up.Zach: I dried up. It happens to writers.Alex: Oh, so you bury yourself with the first young female that comes along, in the hopes she's going to magically restore your lost talent? ...I threw out that typewriter because it represents everything that could have been loving and lasting, and wonderful, and everything that wasn't.

There's so much that can be unpacked from that exchange.

1. We are at our best as writers when we turn to the words and the stories to find ourselves.

At the first sign of becoming "dried up," Zach turns away from the work and to the 'other' -- in this case, booze and sex. But it doesn't matter what the other is. It will be different for each of us when we feel that dried-up feeling. For me it's TV. I simply prioritize shows and movies over my writing because suddenly I'm getting more out of them -- or rather, they're not demanding anything of me like the stories do.

I know, just like you, that what is best for me in these times is to sit in front of that screen or piece of paper and put down some words, any words, and make progress until the joy of writing returns and the broken synapse between my imagination and my active brain is repaired. But I don't. I take the easy way out. I choose the option that doesn't force me to face my dried-up-ness.

2. We are at our best as writers when we share what we create with those we love.

This could include family or fans. Both are loved, and both are part of a sort of family circle when it comes to writers anyway. We get so much by sharing our work. In fact, just a few words from a fan who likes something we've done (or better yet, are doing currently) can often offset the dried-up feelings just long enough to create again.

3. We are at our best as writers when our work means something.

Usually, this is when our work means something to us, but in Zach's case (at this point anyway) it is based in what his work meant to his marriage. Don't worry though. Zach will spend the rest of the movie trying to find that for himself again.

Again, this can mean different things to different authors. For me, my work represents my chance to be remembered. After I'm gone, someone, somewhere will have read my work and remember me, hopefully, remember me as someone who brought them joy for a bit while they read (and if I did a particularly good job, after they finished and the story stayed with them). For some writers I know, that meaning is their own opportunity to escape into fiction from the stresses of reality. For others, it's the need to create the stories they can't find anywhere else. And the list goes on.

Regardless, the dried-up feeling is one that is common to us as writers. It's the dealing with it, not the running away in the face of it that is crucial. It's a lesson Zach gets from both his therapist and his agent:

Zach: Not being able to screw is as bad as not being able to write.Psychiatrist: Maybe you should try writing again.Zach: What the fuck does that mean?Psychiatrist: I don't know. I'm not the burning bush. I made a suggestion, not a commandment.-------Zach: If you think I'm such a failure, why do you keep on representing me?Sparks: That's like asking a heroin addict why he keeps shooting up. It's because he keeps hoping for that first-time rush, that cherry high, even though he knows he'll never get it again. He's hooked... and he keeps hoping.Zach: Watch out. I may surprise you.Sparks: You watch out. I'm beyond surprises.

I love that word -- "surprise" -- that Zach uses. I love it because it's something I find in each story I write. It's something I find every time a story grabs my brain and keeps squeezing until the plot and characters and themes drip out. It's something I find in the kernel moment when a story shifts from a random thought to something that begins to take shape in a way I can't even fathom yet.

For me, that "surprise" IS the high of writing. It's the drug I chase as I create fiction, as I tell stories. It's to me what C.S. Lewis defined as joy: "“Child, to say the very thing you really mean, the whole of it, nothing more or less or other than what you really mean; that’s the whole art and joy of words.”

It's a lesson Zach isn't ready for at the beginning of the movie when is trying to explain all that is going wrong in his life that is keeping him from producing the very work that will bring him what he is missing. He tells his agent a litany of horrible situations, only to have him respond: "Don't say it, dear boy, write it."

Pow. Right in the gut.

No comments:

Post a Comment